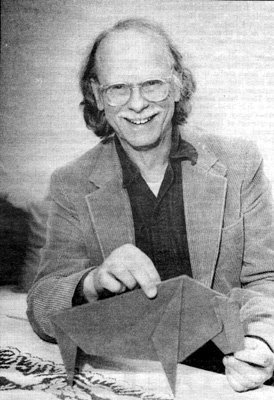

Sam Randlett.

Wauwatosa origami artist helped set standards

Since the 1960s,he's taken paper folding to masses

By Terry Lorbiecki, Wauwatosa News-Times, Wisconsin

When Americans get around to naming National Treasures as the Japanese do, Wauwatosa resident Samuel Randlett will make a good candidate. An early advocate of the traditional Japanese art of paper folding known as origami, he helped standardize the symbols used by hobbyists all over the Western world.

Randlett and his wife, Corrine, live at 2001 N. 72nd St., Wauwatosa. He's «half-retired," but still teaches an adult students' music class, the Arts and Liberal Studies Program, at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and has a number of private piano students. His almost-completed. doctoral studies in music were set aside after his first wife died in the late 1960s.

Randlett and his wife, Corrine, live at 2001 N. 72nd St., Wauwatosa. He's «half-retired," but still teaches an adult students' music class, the Arts and Liberal Studies Program, at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and has a number of private piano students. His almost-completed. doctoral studies in music were set aside after his first wife died in the late 1960s.

Music is one of his pleasures and origami is another. On top of a parlor grand piano in a small music room he keeps a paper cutter, the must-have implement of all paper folders. «I love square paper. . . » Randlett said, -

Paper is the sole element, of origami and more often than not, it's square. With a few simple folds - or for experts, many complicated folds - a square is transformed into a bird, a flower, a dinosaur or anything the eye can see or the fancy devise.

The joy of origami, said Randlett, is the triumph of the imagination over seemingly insuperable obstacles. Lying half-way between art and play, between sculpture and a game, paper folding appeals to children but also to engineers and mathematicians.

Ranfflett discovered origami as a child in the mid 30s when another boy taught him to fold a bird. He learned a second fold from a Book of Knowledge bought second-hand during the depression years and then all progress stopped

He said, "These days if you are interested in learning the yo-yo there's a Smothers Brothers video. You plug it in and you learn. But back then, there was really nowhere to go and I didn't have the genius to develop farther on my own."

He was not, he continued, like his friend, Fred Rohm, an engineer who stopped smoking and had to do something with his hands and so took up paper folding - becoming in the process, a proficient and well known American practitioner.

Randlett found his way back to origami via his interest in magic. Rohm was just one of origami greats he met in the 60s when the art was just beginning to open up. Other international figures he's known are Lillian Oppenheimer, Neale Elias, Robert Neale, John M. Nordquist and Robert Harbin.

Where their names appear, his does too. In the 1964 book "Secrets of Origami - The Japanese Art of Paper - Folding," by English paper folder Robert Harbin, Randlett's four books are listed among 'the best of Western publication." Of the three authors named, Randlett is the only American.

One of his books, "The Flapping Bird", consists of newsletters published in the late 60s through the 70s. The book features diagrams by his first wife, Jean Randlett, and several models created by other family members. Among them are his second wife, Thelma (now also deceased) and his daughter, Susan.

Authorship, according to Randlett, isnt as glamorous as it might seem. 'The glory of writing a book is that once in two years you might hear from a child or get a letter

Another Randlett venture was a series of origami classes for public television on Channel Ten. Since then, the programs have been seen in many parts of the country. The original tapes were erased, but a friend tracked copies down in libra ries and other places and put them on video tape.

Origami devotees still recall watching Randlett, slender and very solemn, demonstrating the valley folds and mountain folds that, like magic, turned paper into something interesting or beautiful *

"There,wasn't much to be happy about those days," Randlett said. "Jean died in 1969 and I had four children to raise. I was exhausted and there was no capacity for editing (the segments). (On the set) it was loaf and loaf and then hurry up. We had 27 minutes to complete the show. It was on tape, but it was done live.»

Although origami has been known for hundreds of years in Japan, it was introduced to the Western world just a little more than a century ago. In the 60s and 70s, there were only a few dozen paper folders in the entire world. Randlett knew most and has remained in contact with them. «I have a lot of friends," he said. 'Me trouble is they're scattered all over the world.» -

Standardizing diagram symbols was one of the most notable accomplishments of modern paper folders. The Japanese master(1), Akira Yoshizawa(2), formalized the basic folds and the English folder, Robert Harbin, adapted them for Westerners.

Randlett said, with some modesty, that his part was to "touch up" Harbin's work.

Randlett's favorite model is one he created - the flapping bird. Pull the tail in and out and its wings, well, flap. He doesn't do much folding these days. «After a while,» he said, "you just look at the diagrams and you know how things go." His chief contribution to the world of origami is as an "editor," sharpening up and critiquing the work of renowned creative paper folders.

Meanwhile, origami is quietly practiced by small pockets of people all over the world. Randlett said, "Every sizable city has a club and there are national and international gatherings

"Do I go? he said. 'No. . . I like to stay at home.

Home may be a good place for a National Treasure to be.