![]()

![]() He looked around, as if he was seeing the world for the first time. Beautiful was the world, colourful was the world, strange and mysterious was the world! Here was blue, here was yellow, here was green, the sky and the river flowed, the forest and the mountains were rigid, all of it was beautiful, all of it was mysterious and magical, and in its midst was he, Siddhartha, the awakening one, on the path to himself. All of this, all this yellow and blue, river and forest, entered Siddhartha for the first time through the eyes, was no longer a spell of Mara, was no longer the veil of Maya, was no longer a pointless and coincidental diversity of mere appearances, despicable to the deeply thinking Brahman, who scorns diversity, who seeks unity. Blue was blue, river was river, and if also in the blue and the river, in Siddhartha, the singular and divine lived hidden, so it was still that very divinity's way and purpose, to be here yellow, here blue, there sky, there forest, and here Siddhartha. The purpose and the essential properties were not somewhere behind the things, they were in them, in everything.

He looked around, as if he was seeing the world for the first time. Beautiful was the world, colourful was the world, strange and mysterious was the world! Here was blue, here was yellow, here was green, the sky and the river flowed, the forest and the mountains were rigid, all of it was beautiful, all of it was mysterious and magical, and in its midst was he, Siddhartha, the awakening one, on the path to himself. All of this, all this yellow and blue, river and forest, entered Siddhartha for the first time through the eyes, was no longer a spell of Mara, was no longer the veil of Maya, was no longer a pointless and coincidental diversity of mere appearances, despicable to the deeply thinking Brahman, who scorns diversity, who seeks unity. Blue was blue, river was river, and if also in the blue and the river, in Siddhartha, the singular and divine lived hidden, so it was still that very divinity's way and purpose, to be here yellow, here blue, there sky, there forest, and here Siddhartha. The purpose and the essential properties were not somewhere behind the things, they were in them, in everything.

Hermann Hesse - Siddhartha

![]() The ultimate metaphysical secret, if we dare state it so simply, is that there is no boundaries in the universe. Boundaries are illusions, products not of reality but of the way we map and edit reality. And while it is fine to map out the territory, it is fatal to confuse the two.

The ultimate metaphysical secret, if we dare state it so simply, is that there is no boundaries in the universe. Boundaries are illusions, products not of reality but of the way we map and edit reality. And while it is fine to map out the territory, it is fatal to confuse the two.

Ken Wilber - No boundary

![]() But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.

But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.

Marcel Proust - Remembrance of Things Past.

[Full text] [Original French text]

...face shining in the bamboo grove

![]() The potency of silence, of which he sometimes speaks, as indeed do others, is to be sought in the interval between thoughts, of infinitesimal duration to split-mind, but without, or of infinite, duration, in itself, since it is intemporal. To him who experiences it, it might have any conceivable duration, though to an observer it can have none. In itself it is never a momentary thing, for it is the permanent background of what we experience as time, the reality rather than the background, and in a feeble image, the screen on to which the ever-moving pictures of conceptual life are projected. It's incalculable potency then becomes apparent, for it is no other than whole-mind.

The potency of silence, of which he sometimes speaks, as indeed do others, is to be sought in the interval between thoughts, of infinitesimal duration to split-mind, but without, or of infinite, duration, in itself, since it is intemporal. To him who experiences it, it might have any conceivable duration, though to an observer it can have none. In itself it is never a momentary thing, for it is the permanent background of what we experience as time, the reality rather than the background, and in a feeble image, the screen on to which the ever-moving pictures of conceptual life are projected. It's incalculable potency then becomes apparent, for it is no other than whole-mind.

Ask the awakened | Wei Wu Wei

![]() There is the odd and persistent fact that there it is only a faithful journey to a distant region, a foreign country, a strange land, that the meaning of the inner voice that is to guide our quest can be revealed to us. And together with this odd and persistant fact there goes an other, namely, that the one who reveals to us the meaning of our cryptic inner message must be a stranger, of an other creed and a foreign race.

There is the odd and persistent fact that there it is only a faithful journey to a distant region, a foreign country, a strange land, that the meaning of the inner voice that is to guide our quest can be revealed to us. And together with this odd and persistant fact there goes an other, namely, that the one who reveals to us the meaning of our cryptic inner message must be a stranger, of an other creed and a foreign race.

Heinrich Zimmer

Myths and symbols in India art and civilization

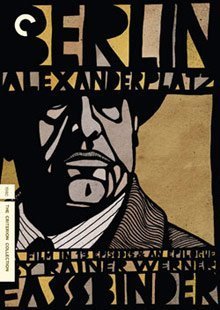

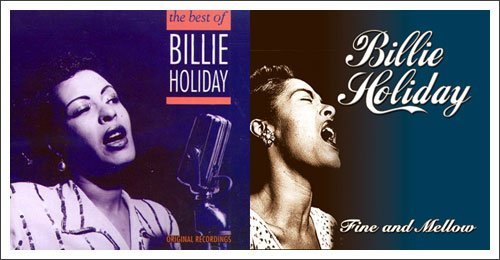

![]() Blood on the leaves, blood at the root

Blood on the leaves, blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the Southem breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant South

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the tree to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

[more...]

![]() "At nineteen I was a stranger to myself.

"At nineteen I was a stranger to myself.

At forty I asked myself: who am I?

At fifty I concluded I would never know."

Edward Dahlberg

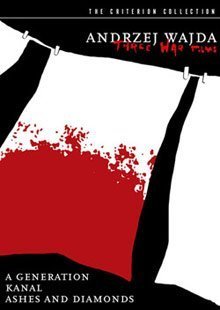

![]() Fernando Pessoa

Fernando Pessoa

A Shrug of the Shoulders

We generally give to our ideas about the unknown the color of our notions about what we do know: If we call death a sleep it's because it has the appearance of sleep; if we call death a new life, it's because it seems different from life. We build our beliefs and hopes out of these small misunderstandings with reality and live off husks of bread we call cakes, the way poor children play at being happy.

But that's how all life is; at least that's how the particular way of life generally known as civilization is. Civilization consists in giving an innapropriate name to something and then dreaming what results from that. And in fact the false name and the true dream do create a new reality. The object really does become other, because we have made it so. We manufacture realities. We use the raw materials we always used but the form lent it by art effectively prevents it from remaining the same. A table made out of pinewood is a pinetree but it is also a table. We sit down at the table not at the pinetree

The Book of Disquiet

![]() A bee settling on a flower has stung a child. And the child is afraid of bees and declares that bees exist to sting people. A poet admires the bee sucking from the chalice of a flower and says it exists to suck the fragrance of flowers. A beekeeper, seeing the bee collect pollen from flowers and carry it to the hive, says that it exists to gather honey. Another beekeeper who has studied the life of the hive more closely says that the bee gathers pollen dust to feed the young bees and rear a queen, and that it exists to perpetuate its race. A botanist notices that the bee flying with the pollen of a male flower to a pistil fertilizes the latter, and sees in this the purpose of the bee's existence. Another, observing the migration of plants, notices that the bee helps in this work, and may say that in this lies the purpose of the bee. But the ultimate purpose of the bee is not exhausted by the first, the second, or any of the processes the human mind can discern. The higher the human intellect rises in the discovery of these purposes, the more obvious it becomes, that the ultimate purpose is beyond our comprehension.

A bee settling on a flower has stung a child. And the child is afraid of bees and declares that bees exist to sting people. A poet admires the bee sucking from the chalice of a flower and says it exists to suck the fragrance of flowers. A beekeeper, seeing the bee collect pollen from flowers and carry it to the hive, says that it exists to gather honey. Another beekeeper who has studied the life of the hive more closely says that the bee gathers pollen dust to feed the young bees and rear a queen, and that it exists to perpetuate its race. A botanist notices that the bee flying with the pollen of a male flower to a pistil fertilizes the latter, and sees in this the purpose of the bee's existence. Another, observing the migration of plants, notices that the bee helps in this work, and may say that in this lies the purpose of the bee. But the ultimate purpose of the bee is not exhausted by the first, the second, or any of the processes the human mind can discern. The higher the human intellect rises in the discovery of these purposes, the more obvious it becomes, that the ultimate purpose is beyond our comprehension.

![]() Mara Mori brought me

Mara Mori brought me

a pair of socks

which she knitted herself

with her sheepherder’s hands,

two socks as soft as rabbits.

I slipped my feet into them

as if they were two cases

knitted with threads of twilight and goatskin,