Origami

A hobby unfolds

Jean-Claude Lejeune's hilltop home is filled with beautiful objects, and some of the most interesting are made of paper.

A large, three-dimensional polyhedron rests on a desk top, the latticework structure made of carefully folded pages of black and white art from an old book.

The structure, folded recently by Lejeune, looks like it came straight from an M.C. Escher graphic.

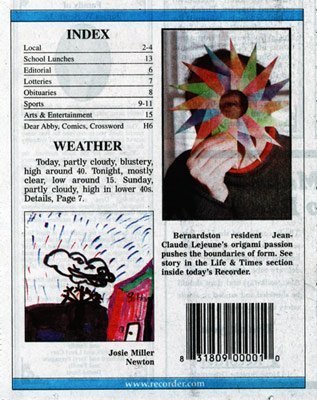

Other items Lejeune has made include a rainbow-colored 16 piece starburst, an Inca mask and a multi-module "paperweight" that makes you feel as though you're looking through a kaleidoscope.

"This is the most democratic craft," Lejeune says of his hobby, origami.

"You can use recycled paper. You can be dirt poor and look what you can create.”

Origami literally means "paper folding" in Japanese, and what many of us think of as a childhood past time has many adult fans as well. Beyond the paper cranes and paper airplanes of childhood, the art of paper-folding has fans of all ages.

"If you ask 1,000 kids and their teachers, everybody has made the Crane," said Lejeune. "If only they knew what's beyond."

Stopping with the crane, he says, is like knowing how to make an omelet without knowing that the same ingredients - flour, eggs and butter - can also be used to make a soufflé and other dishes.

Some folders specialize in three-dimensional stars, cubes, and hexagons using several folded interlocked squares of paper. Others are devoted to folding intricate animals - even lobsters, dinosaurs, dragons. There are "action figures:" beyond paper airplanes, it's possible to fold hand puppets, jumping paper frogs, flapping birds and water bombs that can be filled, for a little while, with real water. Some people like to construct molded, sculptural figures using a “wet folding" technique, in which a thick paper is dampened and carefully shaped during the folding sequence.

Almost anything can be shaped from folded paper - insects, dancers, Valentine hearts, puzzles, picture frames, and gift boxes.

A perfectly square sheet of paper is really the only thing needed to get started, so Lejeune recommends investing in an Exacto knife, and a square Plexiglas template so that all kinds of paper - old magazine pages, aluminum foil, gift wrap, construction paper can be tried.

The square is the most traditional shape, although there are many designs that are fashioned out of rectangles and even out of dollar bills. In the most traditional form of origami, there is no paper cutting- folding is the only technique allowed.

"It's a very simple form, a little square, and there's certain things you have to do," said Lejeune. "There's a boundary you have to work with. A boundary is what form is about. This is where the creativity lives.

There's something between these two edges, where it's like a little war front, but it could be the place where you shape yourself. Resistance isn't always a bad thing."

The art of paper folding probably began soon after the Chinese discovered how to make paper, in the first century A.D. Historians believe Japanese origami probably began in the 6th century, soon after papermaking was introduced. Peter Engel, author of “Origami: from Angelfish to Zen," says origami became a significant part of the ceremonial life of Japanese nobility, from about 794 to 1185, when paper was still a rare and precious commodity that only the rich could afford. For instance, Samurai warriors would give gifts adorned with “noshi” - good-luck tokens of folded paper and strips of abalone or dried meat.

The "democratization" of origami occurred between the 1600s and about 1867, during a renaissance of Japanese art and culture and presumably when paper was more accessible to common people. The oldest surviving publication on origami, the Senbazuru Orikata ("How to Fold 1000 Cranes") is dated 1797.

Paperfoiding was also developed by the Moors, who brought the craft to Spain in the eighth century, but their style focused. primarily on creating geometric figures. Engel notes that origami in the United States has many engineers, architects and mathematicians among its practitioners.

Leonardo da Vinci drew geometric exercises in paperfolding along with the study of the motion of paper airplanes in his notebook. “Alice and Wonderland” author Lewis Carroll, whose real name was Charles Dodgson, entertained children at his country home with toys folded from paper. In the original illustrations in "Through the Looking Glass," the carpenter of "The Walrus and the Carpenter" and a train passenger both sport origami hats.

And magician Harry Houdini published one of the first origami books written in English, “Houdini's Paper Magic," in 1922.

Lejeune was born near Paris and has lived in Franklin County about 15 years, with his family. He had been a profes-sional photogra-pher for nearly a decade, when he turned to origami as a pastime.

"What I was seeing was the dif-ference between a hobby and work," Lejeune said. "For my work, I was sometimes shooting things I didn't care for. I wanted to find something I would do just for the love of it."

Lejeune found a few pages of origami models in a book about paper crafts, and, intrigued, soon bought another book, explicitly about origami. But learning the skills, he said, didn't come easy.

"I was trying to make a Christmas star; and I just couldn't do it," he said. "I was frustrated. I remember throwing the thing in the book, and the first thing I said was, 'I'm never going to do this again. “But I tried one more time, and it worked."

In the 20 years since, Lejeune has continued folding and learning more about the art along the way.

While living in Chicago, Lejeune wrote to Samuel Randlett, a Wisconsin-based author of several origami books, and a man who helped to standardize the instruction symbols for types of origami folds that are used by folders all around the world. Randlett wrote back, and invited Lejeune to attend his weekend gatherings of origami folders.

'Whenever I'd go visit these people, we spent 12 hours making things," said Lejeune who made the two-hour drive to Randlett’s home.

When asked why he drove so far just to do origami, Lejeune replied, "It was like driving for two hours to go to heaven once a week."

He said folders from around the world would send their creations to Randlett, for him to see. "He was a kind of clearing house," Lejeune explained.

Lejeune said those who came would get to look at the new origami creations, then work on their individual projects, getting inspiration from others as they went along.

Most of the people that create origami are very ingenious, he said. "When you make these things, and you have a little experience, you have a little taste of the mind that created them."

Lejeune said he visited Randlett for about five years, until he moved to New England. Lejeune said there's a very tight-knit community of origamists who know each other and who often attend origami conventions.

Lejeune bas taught origami in Paris, to several area school groups and in workshops at the Brattleboro Museum and Sharon Art Gallery, Peterborough, N.H. He says the craft helps to teach children patience and precision.

"I have patience with children who can't do origami, but I have no patience with someone who is sloppy," he said. "I don't think sloppiness has any place in origami."

To do origami well, he said, "you have to come from two dimensions to three dimensions," which is difficult for some to do while learning an origami project from a book.

Lejeune said paper-folders shouldn't be discouraged if a design takes a few tries to master. It's often a good idea to try a new project on scrap paper, saving the best paper for models when you've mastered them.

"There's a saying that goes: If you haven't folded a model 99 times, you haven't folded it yet," Lejeune said. "When you master that model, then you really learn."

"I love remaking a model, just perfecting it. In a sense I like the familiarity of it," he added. "It's like cooking the same meal over again, trying to perfect it. For me, it's a meditation on mindfulness."

When asked how much time he bas spent doing origami, Lejeune said he has no way of knowing. I don't count it," he said. "This is a miracle to me, that you have a simple little sheet of paper, and it's flat, and you put modules of paper together and (the project) opens up. It's like a flower, to me, in the spring. You put (the paper) together, and there's an elegance to it that's absolutely stunning."

Some of Lejeune's work can be seen on his web site, at:

www.ombredor.com/ori/origami.html

Another great web site is that of origami designer Joseph Wu, at:

www.origami.as/home.html.

You can reach Diane Broncaccio at: dbronc@recorder.com or at: (413) 772-0261 Ext. 277.